The Armenian Language Dilemma

Ten-year-old Meline Almasian doesn’t have the perfect remedy for saving the Armenian language from extinction in America. But she does offer one way to preserve the Mother Tongue and keep it solvent: «Go to church, hear the language spoken, and treat it like a learning lesson», she says. «If any language dies, it’s only because people let it die. It’s up to all of us to keep the language alive – young and old.»

Meline joined other students from St. Gregory Church (Philadelphia) in responding to an article penned by this writer as to why the Armenian language might be dying a slow death in America. The article received wide circulation in the Armenian-American press and drew much response from readers.

Like many of her peers Meline attends Armenian School every Sunday at St. Gregory Church and takes advantage of a 45-minute session from her instructors, dividing her schedule with religious bouncy castle education. It isn’t ample time for a language, considering all the distractions one might face in that given period.

In the case of Aghavny Bebirian, the 18-year-old is raised in an Armenian home where the language is spoken regularly. She is quite fluent, as is her younger sister Christina, and feels privileged to be bilingual. «It’s up to our current generation to take the bull by the horns», says Aghavny. «I feel fortunate to have the ability to carry this language into the future. We owe it to our ancestors to keep the heritage alive. And the language is an important part of this heritage. To save it, we must learn it, speak it and, more importantly, pass it along to others.»

In the opinion of John Mahlebjian, the 13-year-old sees how the language has evolved over time and insists people must adapt to changes in our culture. «In order to keep our identity, it starts with the language», he believes. «If we can’t communicate words, we can’t communicate feelings. If parents don’t use it in the home, it’s hard for their children to learn.» Armen Almasian, 12, feels the language should take precedence over other church activities and «talking with a priest». Others like Anna Shahtanian, 10, feel it begins with the basics – simple conversation – then a more advanced form. «A number of reasons can be pointed to the lack of Armenian», states Nairi Hovsepian, 15.

«The fact children have grown Americanized has hurt the culture, along with intermarriages and general apathy toward the language. To save the language, it must become more of an option in schools and community life. We owe that much to our survivors and our genocide victims.»

Meanwhile a rash of opinions have poured forth from readers around the world including Armenia, showing monumental concern over the welfare of the Armenian language in America. Siran Tamakian teaches English as a Second Language at Watertown High School as well as Armenian language classes. According to Tamakian, Watertown is the only public school in the US that offers Armenian as a foreign language. She teaches both reading and writing. With practically no working tools she devises her own materials, including games and worksheets to keep the students interested. «Every year, it’s a struggle to keep Armenian in the program», she says. «It is always slated to become discontinued. Each year, we meet with the superintendent and parents call in to keep Armenian. The past two years, the advanced Armenian curriculum has been turned into a media class so the kids don’t actually learn Armenian. They’re making videos.»

Daniel Devejian suggests we use what technology has to offer as a way of learning the language through the Armenian Virtual College but that «total immersion with the language and country itself is a must».

The AVC offers on-line courses through the Armenian General Benevolent Union to anyone, anywhere, anytime. At the moment there are six languages of instruction, including both Eastern and Western Armenian.

A promotional film by recent award-winning videographer Peter Musurlian explores life at the Manoogian-Demirdjian AGBU School, complemented by interludes of musician Antranig Kzirian playing the oud. He’s buoyant concerning the progress being made toward preserving and perpetuating the language. In contrast Michael Abladian looked for an adult education class on conversational Armenian and found none. He settled for an after-hours class at his church which didn’t live up to expectations. «A noble effort», he concludes, «but none were professional or even good amateur teachers. It turned into a great disappointment. We were trying to spool up our Armenian for an upcoming trip to Armenia and really committed to learning. The language is dying because few Armenian communities offer credible courses or more rigorous structural classes taught by skilled teachers.»

According to Avetis Sahagian the problem with Armenians is self-ingrained and one of division. The only way to save the language is to save ourselves first. «It’s time to adopt Eastern Armenian as the official language for all Armenians», he maintains. «We have two of too many things: two nations (Armenia and Artsakh), two peoples (Eastern and Western), two Catholicoses and two languages. We need to consolidate and unify. Two distinct dialects cause psychological and cultural divisions. We need to end this self-destructive status quo».

It is true that two dialects cause a problem when there are so few Armenians in the world. But, having learned some basic facts about Armenian recently, I fear that it will be very difficult to end the division as Avetis Sahagian hopes for.

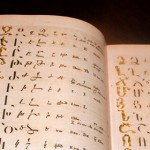

Could the people of the Republic of Armenia return to the classical spelling of Armenian, as some others advocate? Obviously not; a generation has grown up with a phonetic spelling, and they would not willingly switch to an alternative which would require years of effort to learn before they would no longer appear to be illiterate.

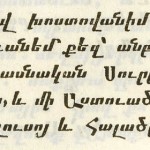

So Eastern spelling is easier, and the diaspora should shift to it, right? But Western Armenian has pairs of consonant sounds like b/p, d/t, g/k… where Eastern Armenian has three distinct consonant sounds, having unvoiced b, d, and g like Chinese. So a Western Armenian speaker would have to learn to pronounce sounds not found either in Western Armenian or, likely, in the language of the country in which he is living.

This is a lot to ask of people who are learning to speak Armenian… to speak to elderly relatives, or to celebrate their heritage… not out of economic necessity, so that success would be imperative. So adding effort to the task would mean fewer people in the diaspora would attempt it.

2product…

…